ENGLISH

WHY

I recently ran a [[design discussion]] on the topic of “How to run good playtests.”

This post is a summary of that discussion.

WHAT

The material here comes from several different sources, which are listed on the last slide as references:

- Valve’s “Secret Weapon“

- Don’t make this assumption about your players

- Valve’s Design Process for Creating Half-Life 2

- MasterClass - Will Wright - Game Design and Theory

- #13 - Playtesting

CONTENT

Table of Contents

This discussion covers:

- The process of [[Playtest]]

- Principles for [[Playtest]]

- Some lessons learned from shares

- And a brief summary

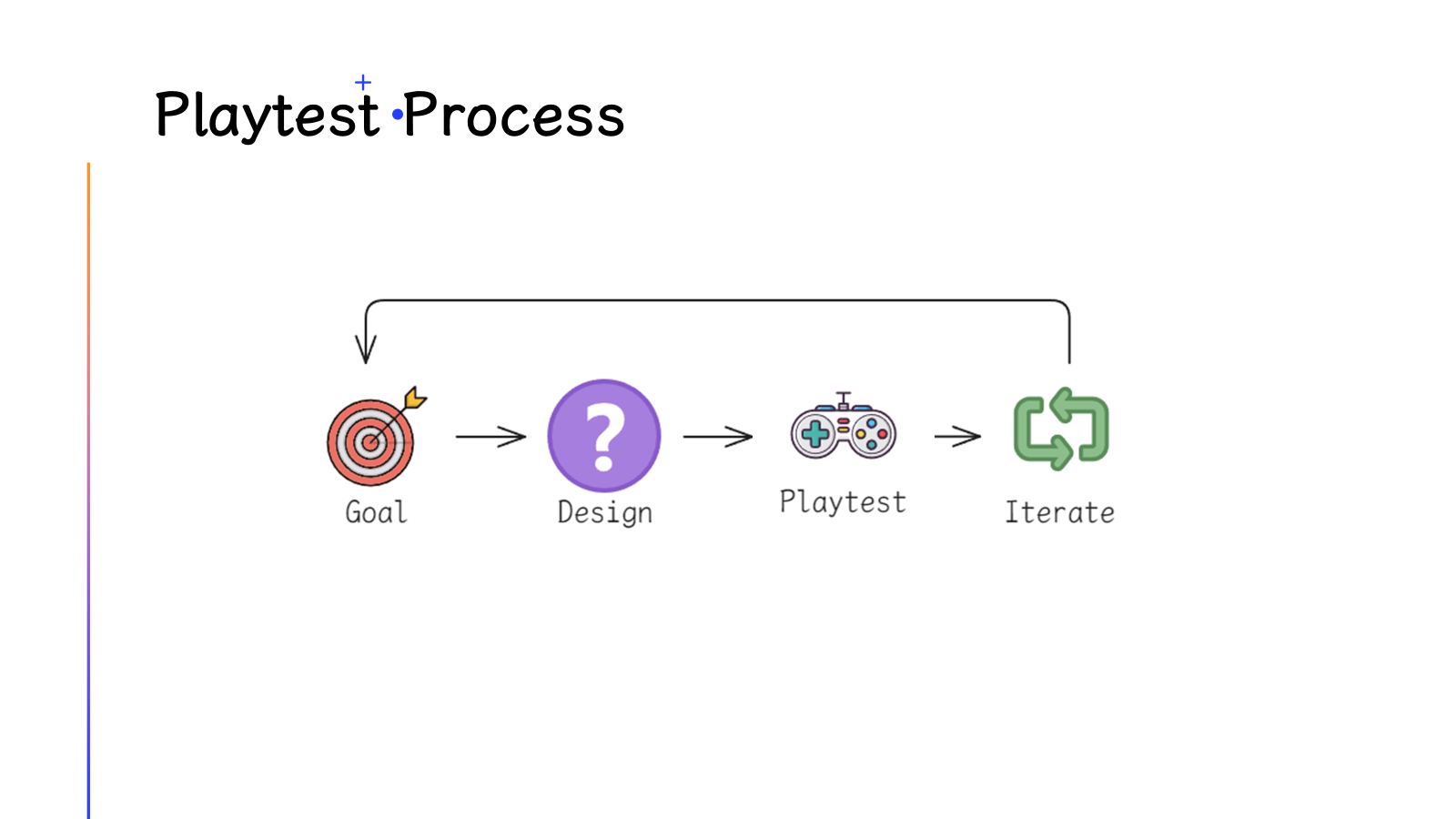

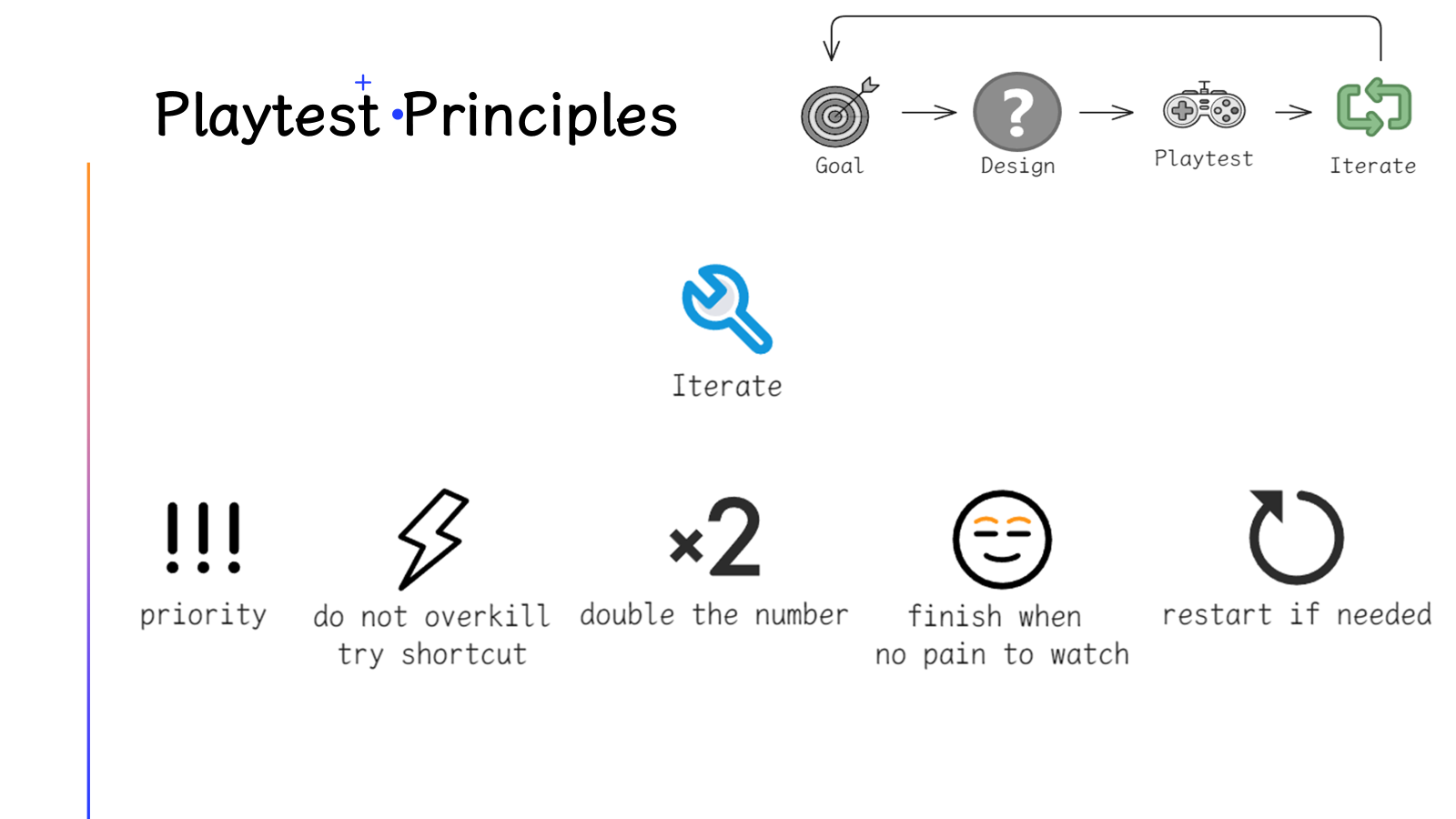

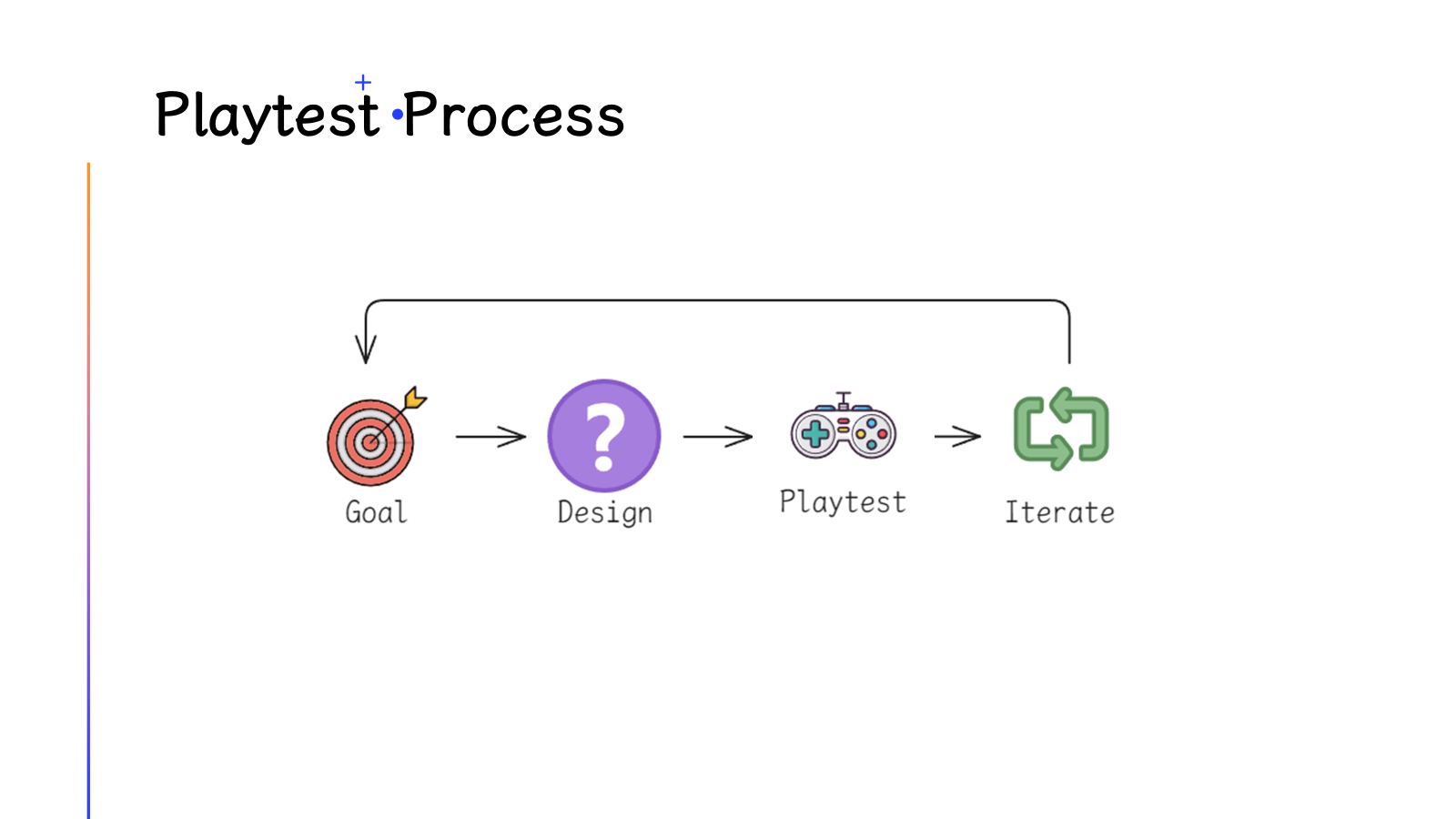

The PLAYTEST Process

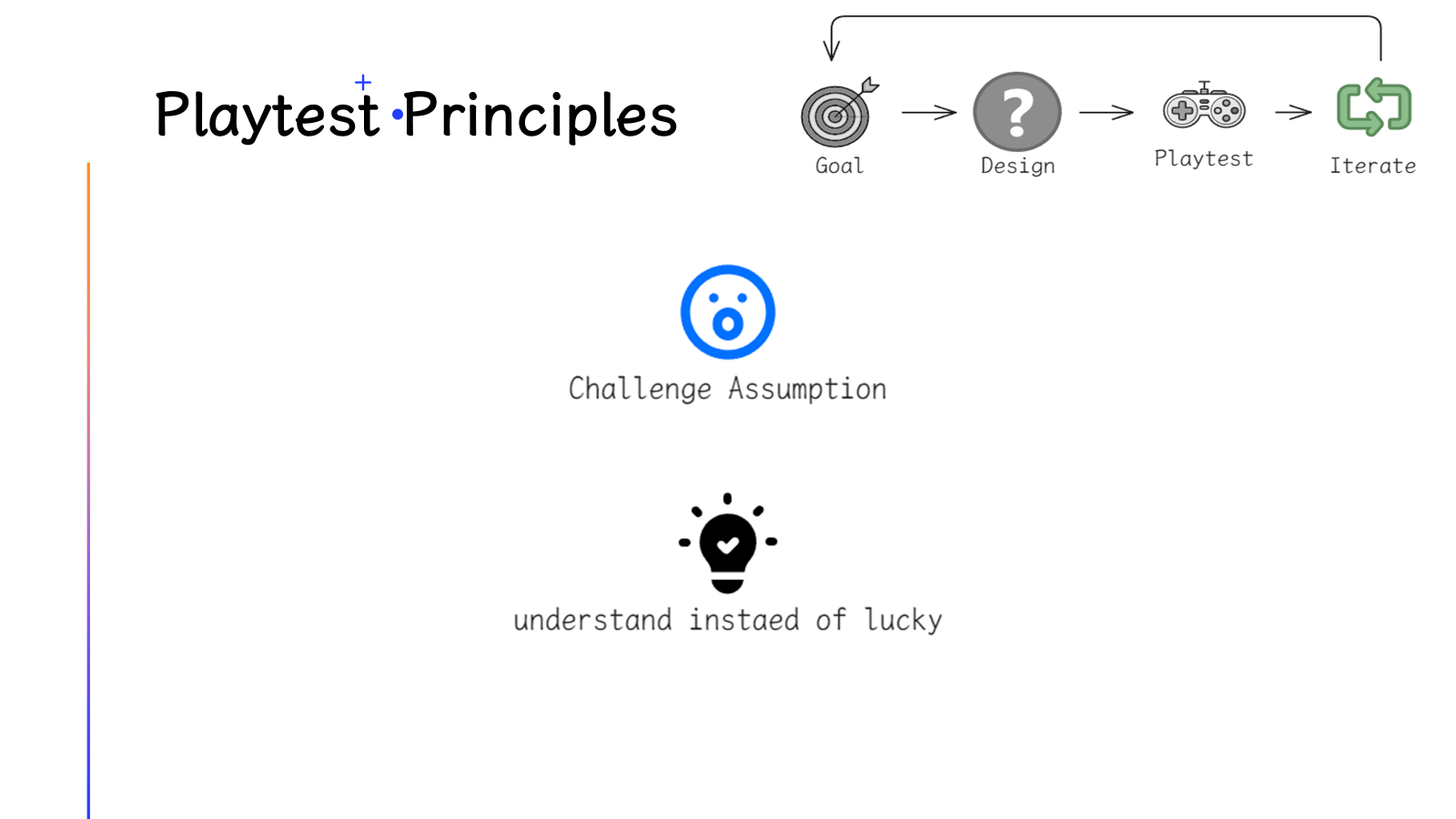

As [[Valve]] describes it, playtesting can be treated as an engineering method for iterative improvement.

The process is basically the same as running experiments:

- Identify the problem (Goal)

- Form a hypothesis (Design)

- Run the experiment (Playtest)

- Iterate based on the results (Iterate)

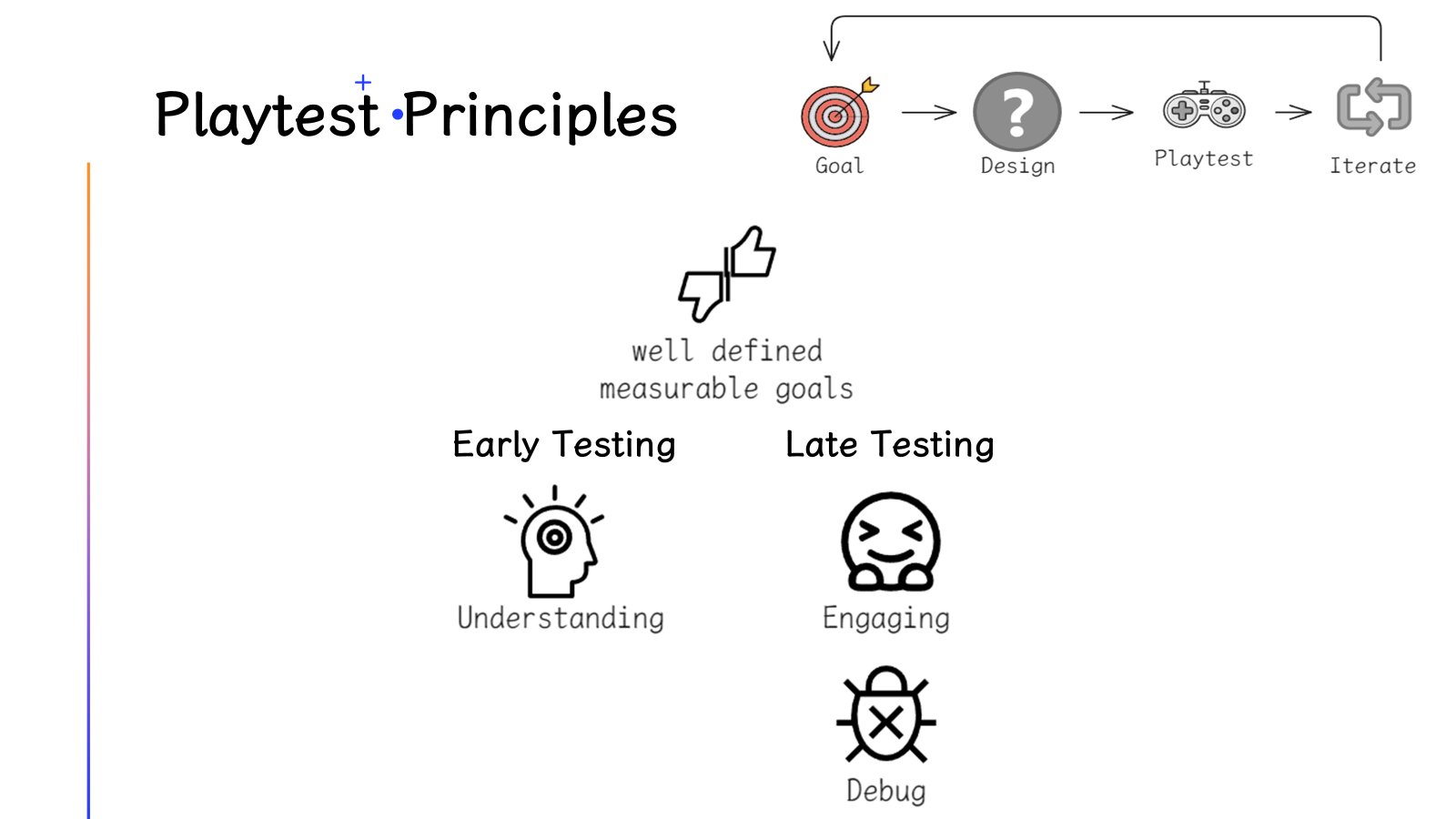

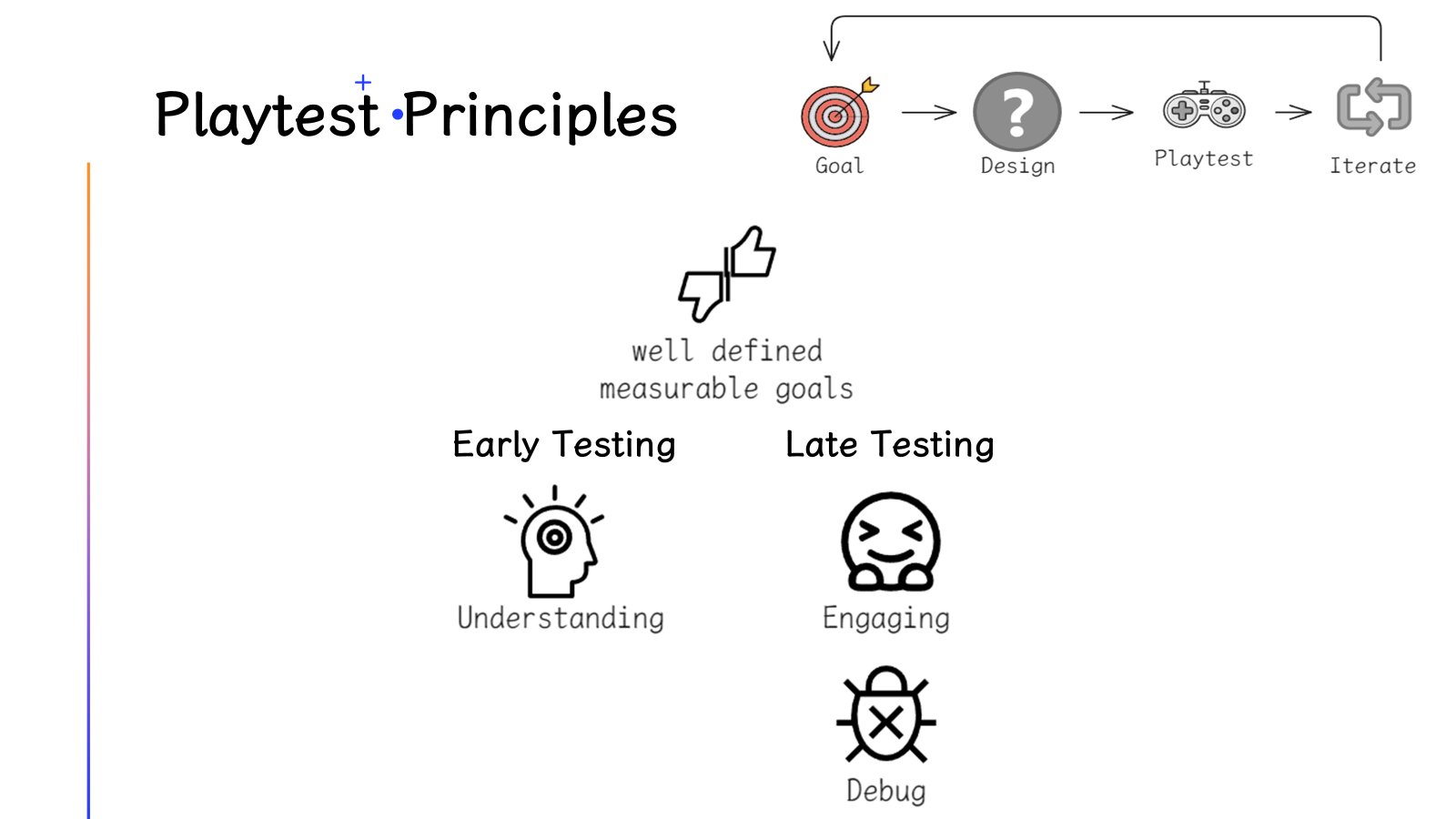

Some Principles of PLAYTEST

Goal

- You should always set clear and measurable goals.

- In the early stages of playtesting, the main focus is understanding – whether players understand what the designer intends.

- In later stages, the focus shifts to engagement – whether players are actually having fun – as well as debugging, i.e., finding potential issues and bugs.

Design

You need to build the right test environment based on the design goal, and avoid interference from irrelevant factors.

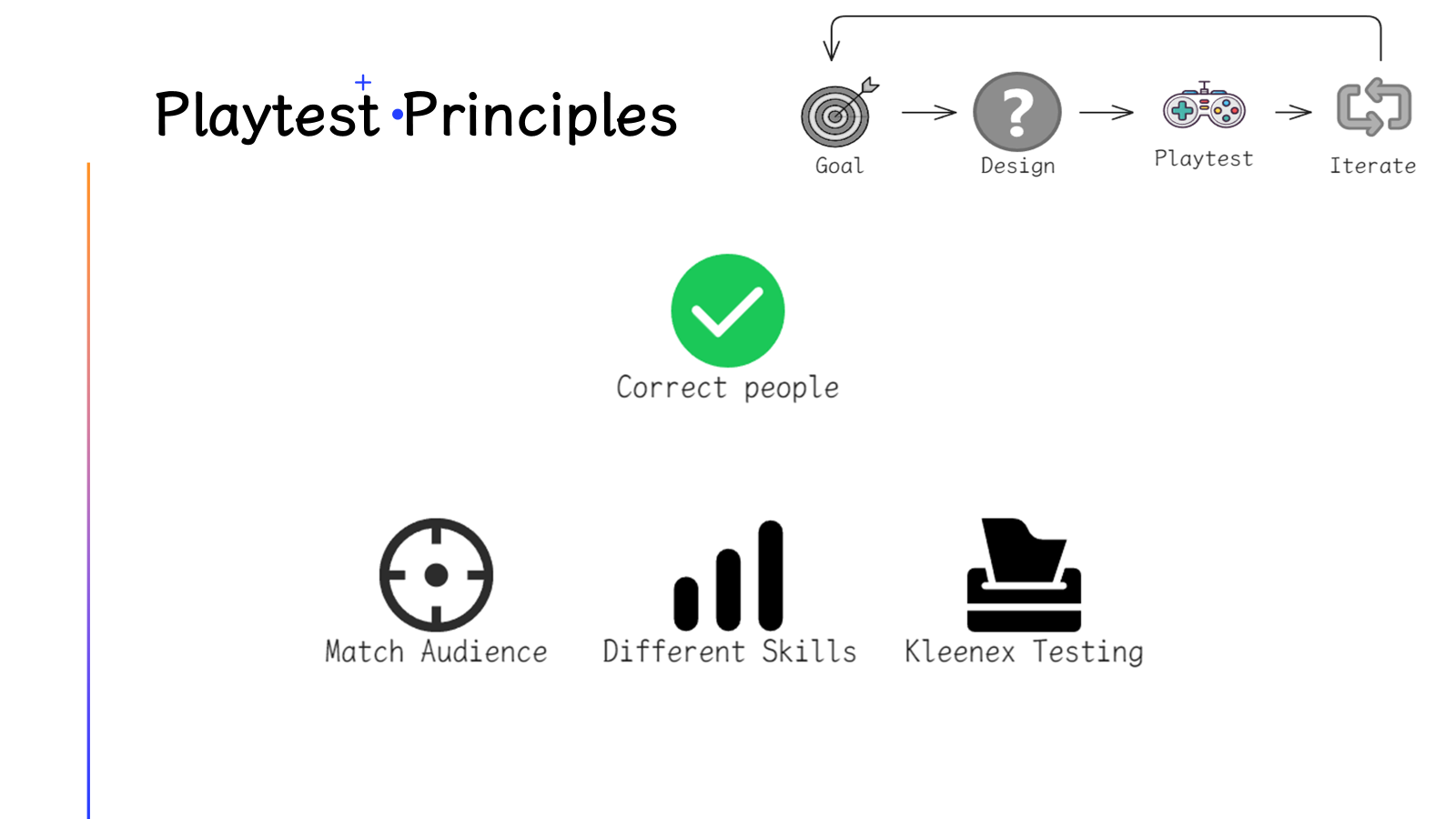

Playtest

- Find the right testers

- Ideally, recruit players from your target audience:

- People who might actually buy and play the game after launch – they best represent the “player voice.”

- For example, [[Valve]] saw people playing shooters in internet cafés as potential target players.

- Involve players of different skill levels

- You need clarity on who the game is really for. Balancing difficulty is hard, so it’s better to let players of different skill levels test it, and make sure the difficulty curve is reasonable.

- Kleenex testing

- Unless you have specific long-term testing needs, testers should ideally only participate once.

- Ideally, recruit players from your target audience:

- Test early

- Valve starts testing as soon as the game is playable, even when everything is still in grey-box.

- Of course, this depends on genre and can be costly that early – but it’s still a useful reference.

- Test frequently

- Valve basically tests every one or two weeks – you could say their development is driven by iterative playtest feedback.

- Filter out outliers

- Only when the sample size is large enough can the data truly reflect reality.

- If I remember correctly, they usually had around five testers per session.

- Unbiased testing

- Get as close as possible to a real play environment

- It’s ideal if you can simulate the final conditions players will experience, though that’s often hard. Still, it’s worth treating as a refernce.

- Give players time to practice

- Especially if you’re testing mid- or late-game content, you must give players time to get familiar with the 3Cs and any ingredients they’ll need.

Otherwise they’ll underperform simply due to unfamiliarity, and the results will be misleading.

- Especially if you’re testing mid- or late-game content, you must give players time to get familiar with the 3Cs and any ingredients they’ll need.

- Shut up and watch

- During tests, apart from necessary help (such as warning about known critical bugs or helping when the player is completely stuck), developers should mostly just watch and not comment.

- Only then can you see the most realistic player behavior.

- And if watching the session feels painful, that usually means the test is valuable – it’s revealing real problems and motivating you to iterate.

- During tests, apart from necessary help (such as warning about known critical bugs or helping when the player is completely stuck), developers should mostly just watch and not comment.

- Get as close as possible to a real play environment

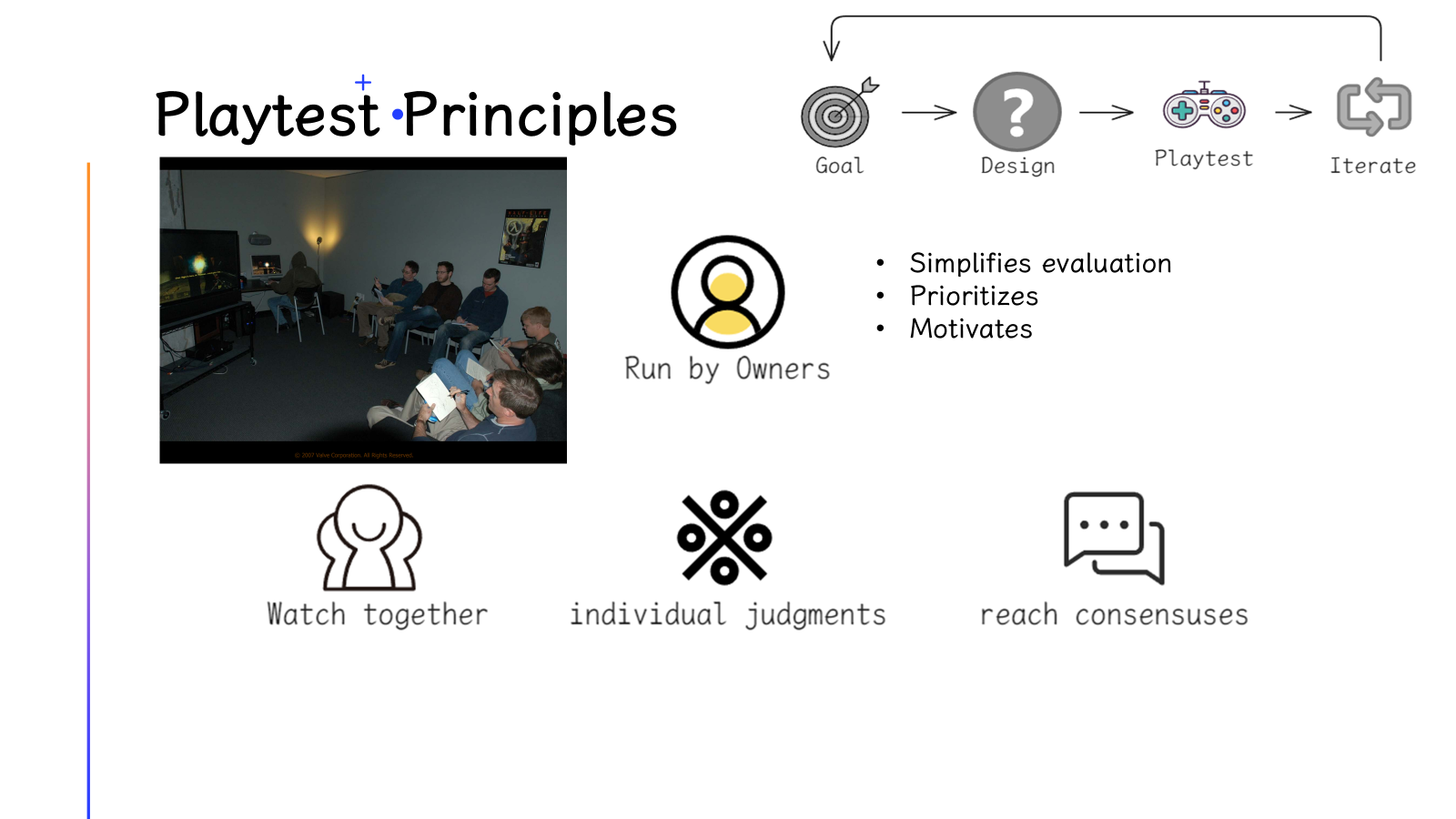

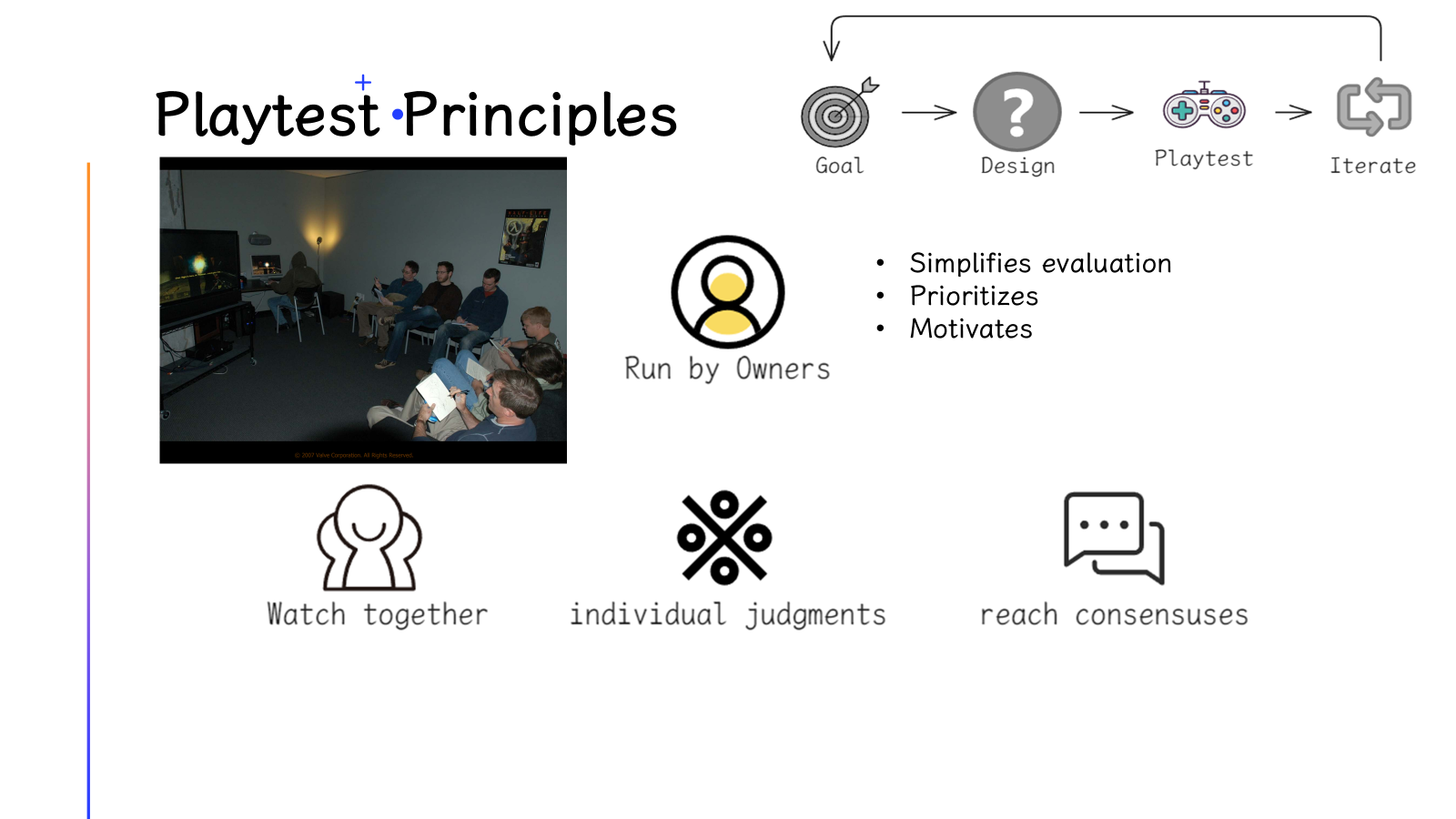

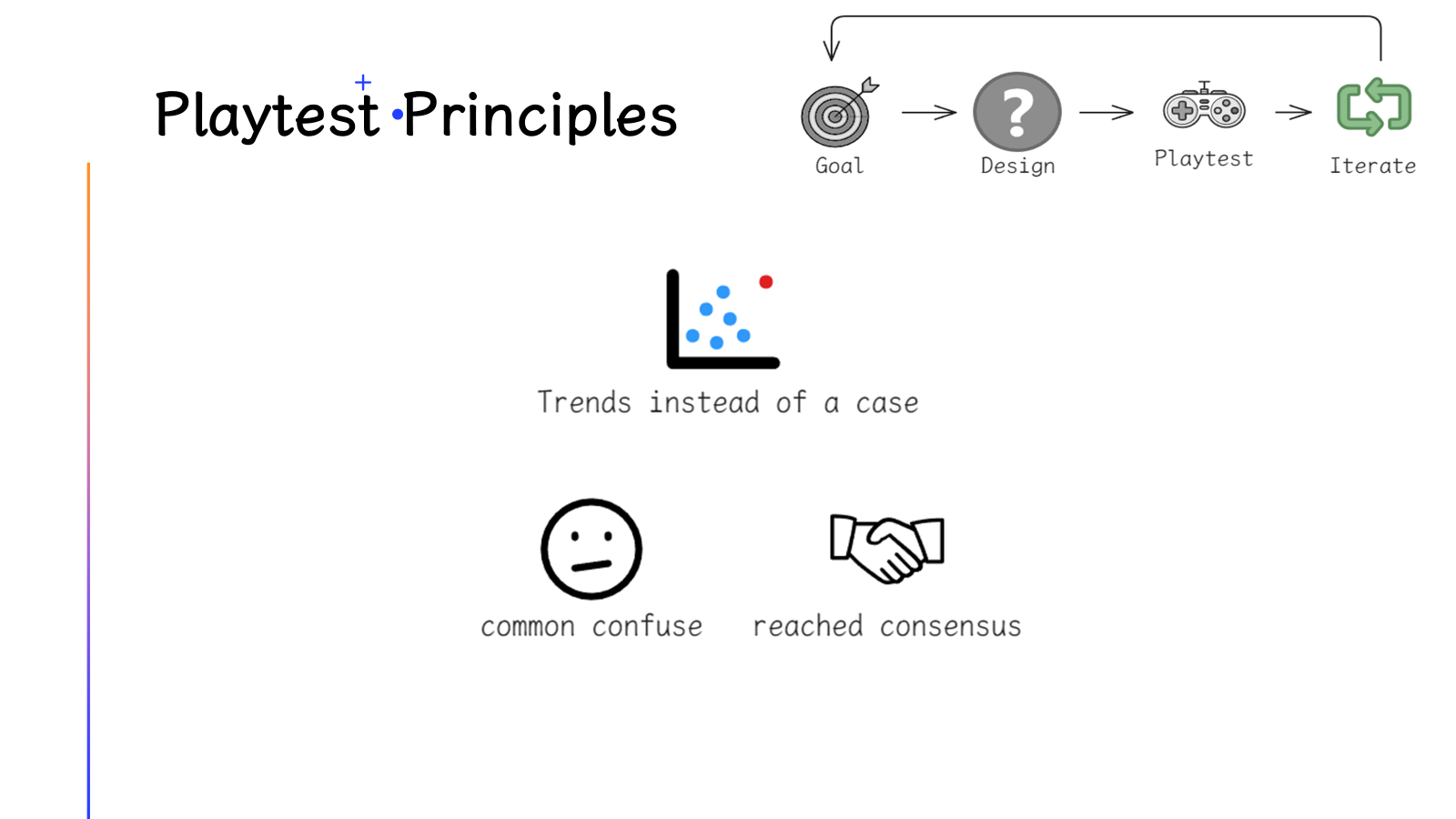

- Involve the key stakeholders in PLAYTEST

- Let the leads and owners watch together.

- Everyone can form their own conclusions.

- Then you can discuss and align on concrete iteration plans.

- This has many benefits:

- Simplifies the evaluation process.

- Helps define priorities.

- And motivates the whole team to keep improving.

Iterate

- Question your assumptions

- Make sure players truly understand, rather than just “getting lucky.”

- Trust trends, not outliers

- Iteration should target the confusion shared by many players.

- Or focus on issues where the dev team has reached consensus.

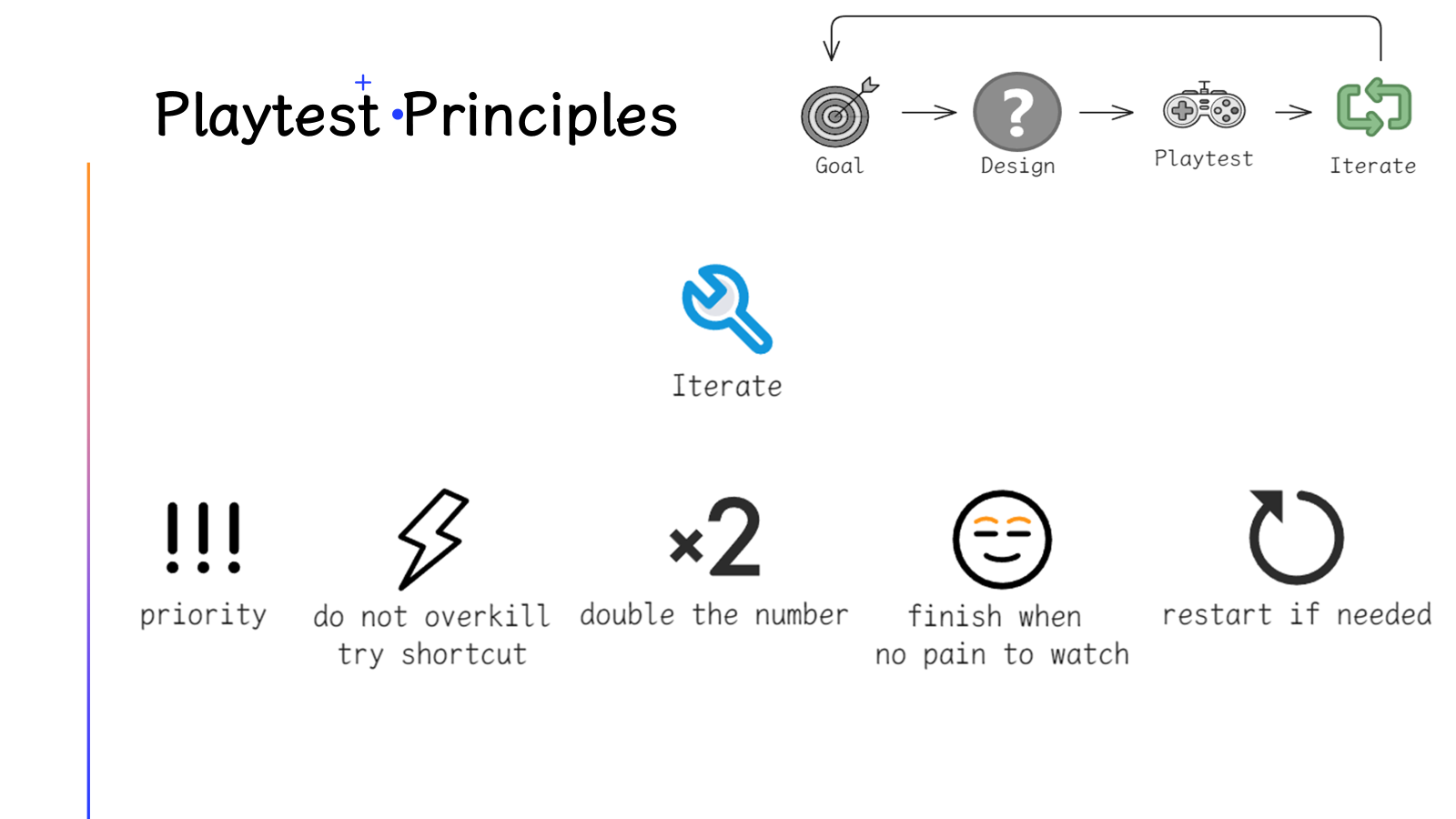

- Some notes for iteration:

- Iterate in order of priority

- That way you can address the biggest pain points fastest.

- Some low-priority issues may even disappear once the major problems are fixed.

- Prefer cheap and fast hacks (1 day of work for 60/100 of value) over expensive and “perfect” solutions (5 day of work for 80/100 of value)

- This is especially important early on, when many things are not yet set stable.

If you can patch things with a quick-and-dirty fix, do that first and avoid heavy investment in something that might be cut later. - That said, in later stages when the game is more mature, quick hacks may no longer be enough – you’ll have to decide when it’s time for higher-quality solutions.

- This is especially important early on, when many things are not yet set stable.

- Make bold changes

- This mainly applies to tuning parameters. If the trend clearly shows that some values need changing, adjust them by a noticeable amount – “double it” style.

Otherwise the change might be imperceptible, and you risk wasting the next test.

- This mainly applies to tuning parameters. If the trend clearly shows that some values need changing, adjust them by a noticeable amount – “double it” style.

- Acceptance criteria – until it is not painful to watch

- When the devs can watch players without pain, you’ve probably reached the bar for that part and can move on to the next module.

- If necessary, cut your losses and restart

- When the direction itself is wrong, further iteration may be meaningless. In that case, long-term pain is worse than short-term pain – fail fast, learn fast.

- Iterate in order of priority

A Few Lessons from Past Projects

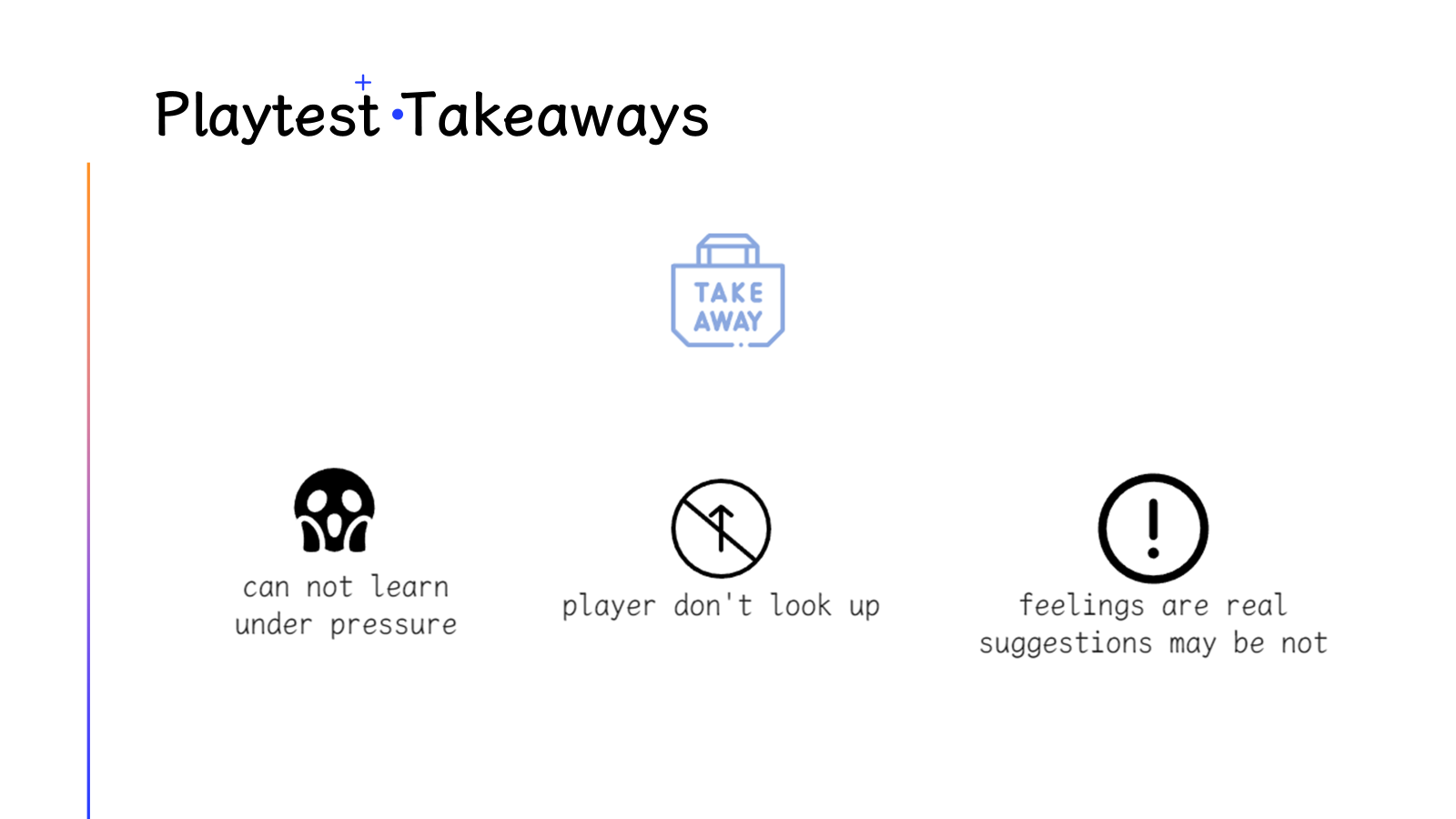

- Players struggle to learn under pressure

- I think I saw this in a GDC talk about [[Destiny]] at some point…

- Players never look up

- This sounds like a joke, but it’s true for many players: most of them focus on what’s at eye level and rarely look upward.

- You can also use this: for example, hide secrets or jump scares above the player’s line of sight.

- Different genres train different player behaviors. Souls-like players, for instance, are used to checking behind doors, above them, and peeking over edges.

These habits come from their past experiences and need to be handled specifically.

- The feelings are always real, but the feedback might not be

- This idea shows up in many domains, from many masters.

- [[Neil Gaiman]] once said something similar: “When people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right.

When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.” - Henry Ford’s quote – “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses” – points to the same thing.

- We also extended this point a bit during the discussion:

- Experts as playtesters

- They’re much more sensitive to hidden problems and may be better at pinpointing the core issue.

- But they might not represent the broader player base.

- Customers as playtesters

- Players may often fail to express their true feelings – out of respect for the devs, or simply because it’s hard to articulate.

- That’s why it’s crucial to carefully observe their reactions while playing and treat that as your primary source of truth.

- Experts as playtesters

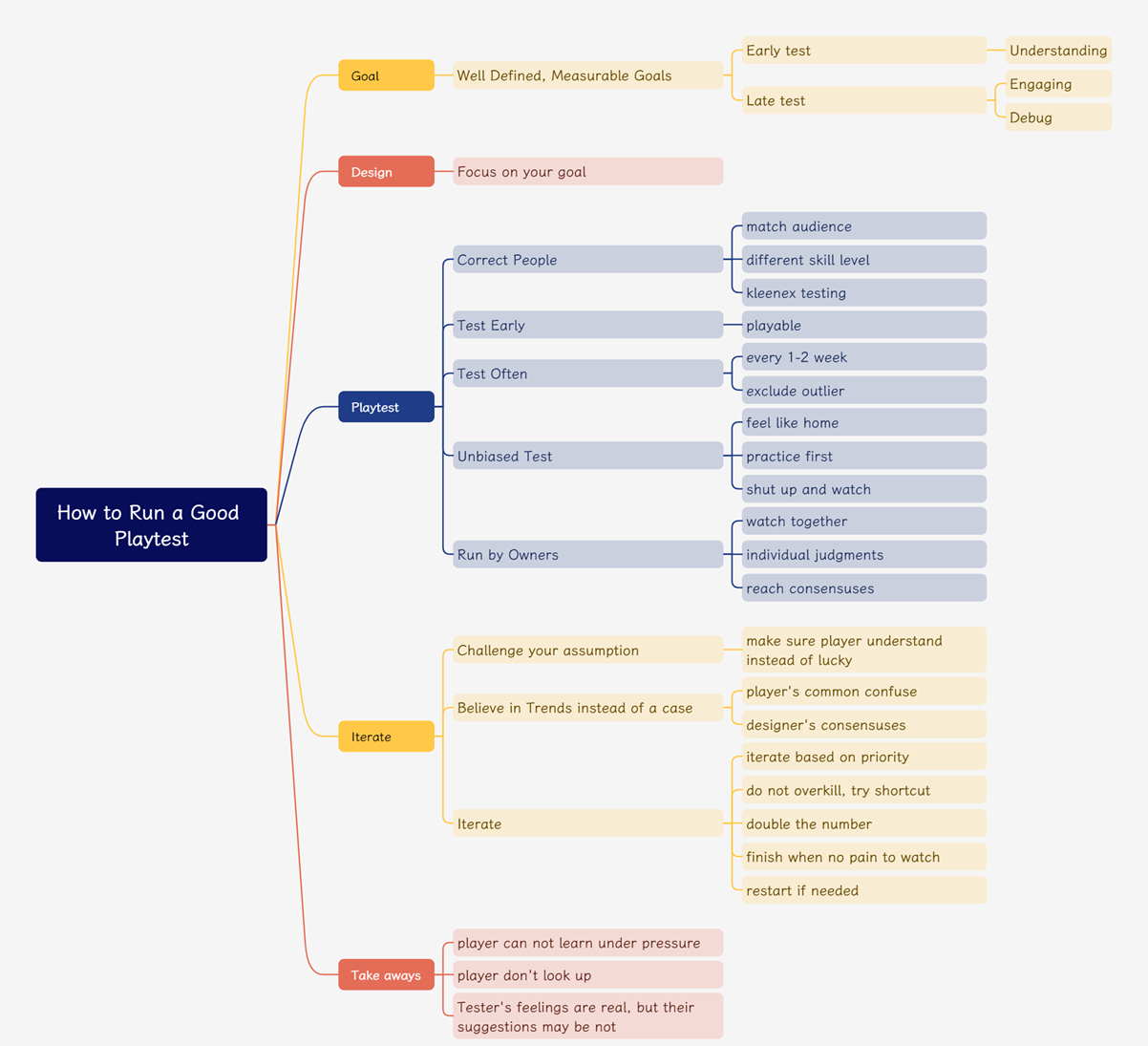

Summary

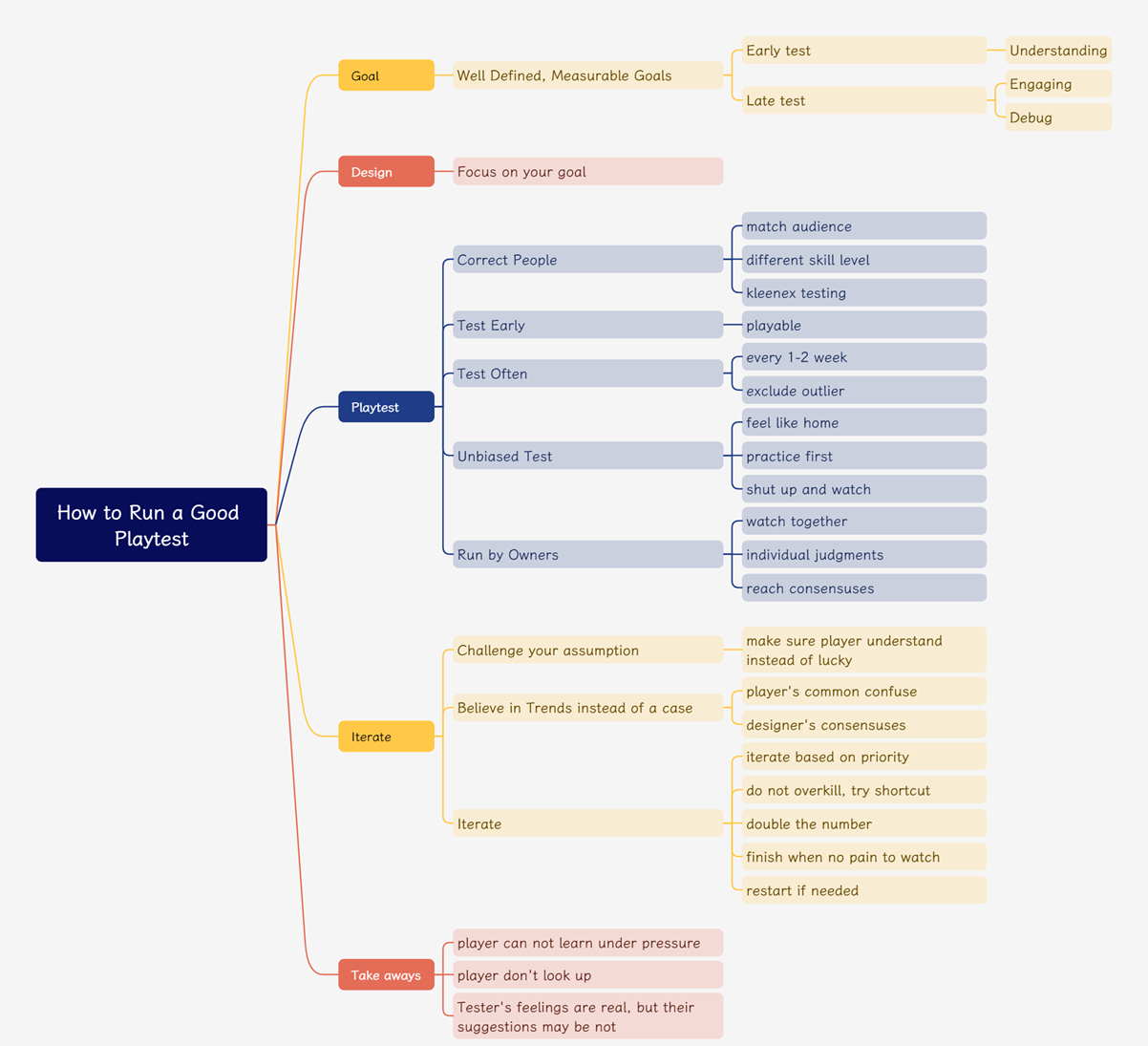

This mind map is a condensed summary of everything mentioned above.

Closing Thoughts

It’s always valuable to compare and synthesize shared experiences from different developers.

But how you actually apply them still depends on your own project and context.

Keep learning, keep moving forward!

中文

WHY

最近以“如何进行好的 Playtest”为主题进行了一次 [[design discussion]],这里将内容进行一下汇总。

WHAT

这次的的内容是从不同地方学习到的,在最后一页中也标注了 References:

- Valve’s “Secret Weapon“

- Don’t make this assumption about your players

- Valve’s Design Process for Creating Half-Life 2

- MasterClass - Will Wright - Game Design and Theory

- #13 - Playtesting

CONTENT

目录

会涵盖以下方面:

- [[Playtest]] 的过程

- [[Playtest]] 的原则

- 一些过往总结的经验

- 以及总结

PLAYTEST 的过程

如 [[Valve]] 所提的,PLAYTEST 可以作为一种工程学方法来对游戏进行不断迭代优化,所以过程就和做实验一样:

- 发现问题(Goal)

- 提出假设(Design)

- 进行实验(Playtest)

- 根据结果进行迭代(Iterate)

PLAYTEST 的一些原则

Goal

- 应该设立明确且可量化的目标

- 在早期的 PLAYTEST 中应该关注的是 understanding - 即玩家是否理解设计者的意图

- 而在后期的 PLAYTEST 中应该关注的是 engaging - 玩家是否玩的开心;以及 Debug - 即找到可能存在的漏洞

Design

需要根据设计的目标来创建合适的测试环境,避免无关因素的干扰

Playtest

- 需要找到合适的测试玩家

- 最好能找到目标受众

- 即那些本可能在发售后进行购买游玩的玩家,他们最能反映“玩家之声”

- 比如 [[Valve]] 觉得网吧中那些在玩射击游戏的玩家就是潜在的目标玩家

- 需要不同水平的玩家

- 需要明确你的游戏到底为谁而做,难度的平衡是一个难题,所以最好能让不同水平的玩家都进行测试,确保难度的合理性

- 一次性测试

- 除非一些特殊的需要长线进行的测试,应该尽可能只让测试者参与一次测试

- 最好能找到目标受众

- 尽早测试

- valve 在游戏达到可玩状态后就会开始测试,即使当时还都是白盒

- 这当然和游戏类型有关,如此早期开始测试也有很高的成本,但依然可供参考

- 频繁测试

- Vavle 基本会每一到两周进行测试——可以说他们的开发也是一种基于测试反馈而进行的迭代开发

- 排除异常值

- 只有达到的一定的样本量之后,才能真实反映最终的数据情况

- 没有记错的话,他们每次测试的人数大概也会在 5 人左右

- 非偏测试

- 尽可能接近真实的游玩环境

- 如果能尽量模拟玩家最终游玩的条件是最好不过了,但这很难实现,所以就是作为某种参考

- 让玩家有机会练习

- 特别是如果测试内容是偏游戏中后期的内容,那么就一定需要给玩家一些时间提前对 3C 以及可能用上的 ingredients 进行试玩和熟悉,否则玩家很可能因为不熟悉而导致没能发挥真实水平,导致结果失真

- 闭嘴观看

- 在玩家测试过程中,开发者们除了进行必要的帮助(比如提前告知一些已知的严重 BUG,以及当玩家完全卡住寻求帮助)之外,应该尽可能地只进行观看而不发表任何观点

- 这样才能够反映最真实的游玩情况

- 而且如果在此期间你看得越难受,说明此次测试确实有一些独到的价值(既帮助你发现了一些问题,又刺激了你努力进行迭代修改)

- 在玩家测试过程中,开发者们除了进行必要的帮助(比如提前告知一些已知的严重 BUG,以及当玩家完全卡住寻求帮助)之外,应该尽可能地只进行观看而不发表任何观点

- 尽可能接近真实的游玩环境

- 让负责人们一起来实施 PLAYTEST

- 大家可以一起进行观看

- 并且分头得出自己的结论

- 最终可以讨论来得出最终的迭代方案

- 好处多多

- 既可以简化评估流程

- 帮助确定优先级

- 也能够激励大家继续迭代修改

Iterate

- 质疑你的预期

- 要确保玩家是真的理解而不是“撞大运”

- 相信趋势而不是极端情况

- 迭代的目标应该是玩家们共有的困惑

- 或者是开发者们达成的共识

- 迭代时的一些要点

- 根据优先级来进行迭代

- 这样能最快解决最棘手的痛点

- 有一些优先级较低的部分很可能在前面的问题修好之后也不再需要关注了

- 尝试便宜而快速的捷径(30 分花费 60 分效果)而不是贵但完善(80 分花费 90 分效果)的方法

- 这一点在早期尤为重要,因为在这时很多东西还未定型,所以如果存在便宜且快速的“补丁”,那么就应该优先这么做,避免大量投入之后最后被验证出这部分内容有可能是不需要的,导致资源的浪费

- 但这一点也要辩证的看待,如果已经是比较成型的阶段,便宜且快速的方案已经不足以满足要求,那也需要考虑是否需要考虑更好的方案进行迭代

- 大刀阔斧的修改

- 这一点针对的是某些参数的修改,当趋势表明有一些参数需要修改时,那么尽可能以“加倍”的方式来对数值进行修改,这样能够确保改动是可被感知的,否则很有可能“改了和没改一样”,浪费下一次测试的结果

- 验收标准 - 直到不再痛苦

- 当开发者们能够在观看玩家测试时不再感到痛苦,那么可能就达到了验收标准,可以推进到下一模块的迭代

- 如有必要,短痛重开

- 很多时候如果方向错误了,再迭代可能也是无用的,那么长痛不如短痛,fail fast, learn fast

- 根据优先级来进行迭代

一些过往经验

- 玩家们在危急关头很难学会东西

- 这一点好像是在看命运的某期 GDC 看到的哈哈…

- 玩家们从不抬头看

- 这一看起来是笑话的点其实对于很多玩家来说都适用,玩家们更多只会关注水平范围的内容,而不会抬头查看

- 这一点当然也可以被反过来利用,比如把需要藏起来的东西或是 jump scare 放在上方

- 对于不同游戏类型的玩家当然有不一样的玩家行为模式,比如熟悉魂类游戏的玩家总是习惯查看门的背后和上方,以及会去路径的边缘部分向下看,这些都是玩家们在不同游戏中练就的行为模式,需要有针对性地应对

- 感受都是真的,但是反馈未必是真的

- 这一点其实在很多不同的场景被很多不同领域的大师们反复提及

- [[Neil Gaiman]] 也曾分享过类似的观点“当人们说哪里感觉不对时,他们通常是对的;但当他们告诉你怎么更改时,他们通常是错的”

- 亨利福特名言“用户只知道他们想要更快的马,但他们不知道他们想要的其实是汽车”也是一个道理

- 这里我们当时也进行了一些延伸讨论

- expertise as playtester

- 他们对其中可能潜藏的问题更加敏锐,并且有机会更准确地指出问题的核心

- 但他们很有可能不能代表广泛的玩家群体的意见

- customer as playtester

- 玩家作为测试者很有可能由于种种原因(对开发者的尊敬、不能准确表述感受等)无法真实反映内心感受

- 所以很重要的一点就是仔细观看他们游玩时的反应,并以此作为最重要的依据

- expertise as playtester

Summary

这是一份总结的思维导图,涵盖了前面所提到的所有内容

小结

总结不同的开发者们的共同经验总是有益处的,但最终如何落地,还是要结合具体情况具体分析。

持续学习,继续前进!